Endotracheal Intubation

Comprehensive endotracheal intubation guide for paramedics and nurses - equipment, technique, troubleshooting, and safety protocols.

Comprehensive endotracheal intubation guide for paramedics and nurses - equipment, technique, troubleshooting, and safety protocols.

Endotracheal intubation (ETI) is the placement of a flexible plastic tube (endotracheal tube or ETT) into the trachea through the mouth or nose to establish and maintain a patent airway. This advanced airway procedure is one of the most critical interventions in emergency medicine, critical care, and anesthesia.

Endotracheal intubation serves multiple vital functions:

Endotracheal intubation becomes necessary when less invasive airway management techniques are insufficient or contraindicated. Common scenarios include:

Failure to maintain or protect the airway:

Respiratory failure:

Trauma indications:

Medical emergencies:

Anticipated clinical course with high risk:

There are few absolute contraindications to intubation when it's truly indicated, but be cautious with:

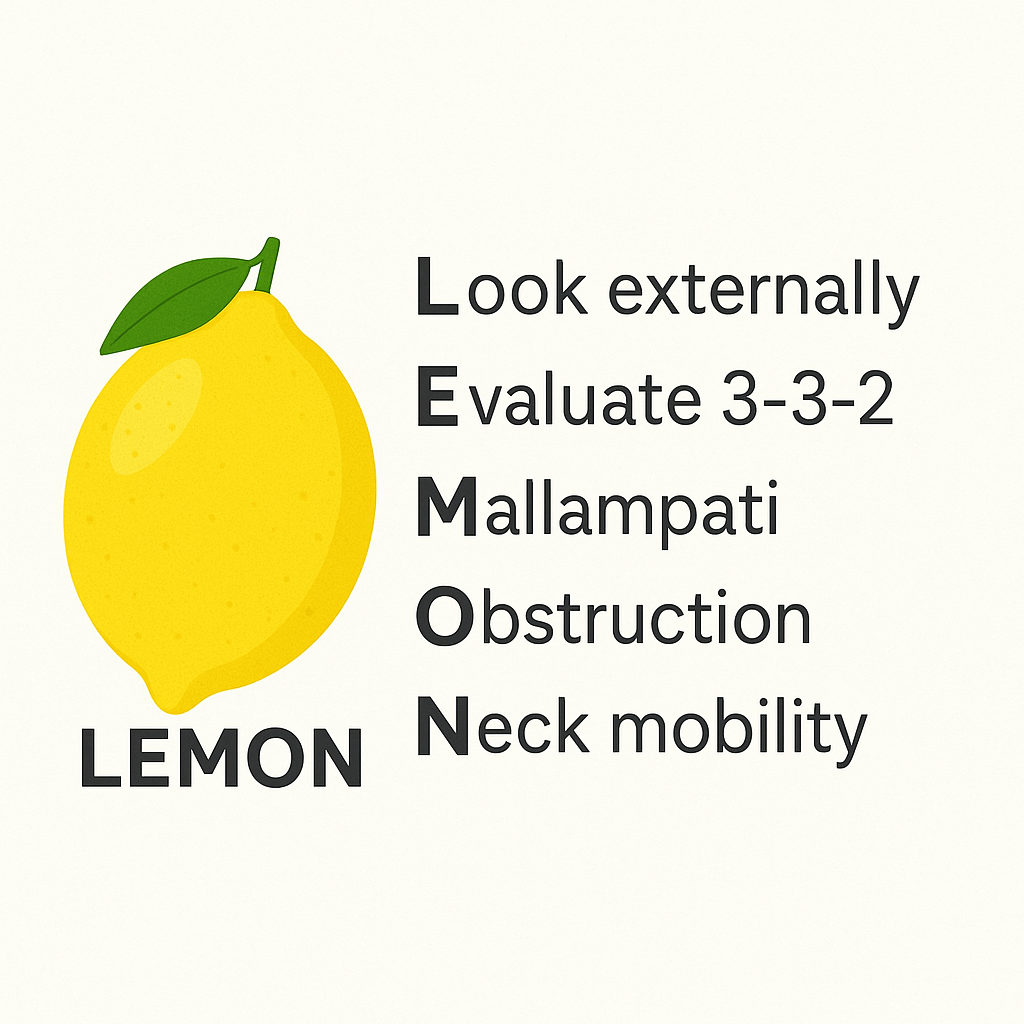

Systematic airway assessment helps identify potential difficulties before the first laryngoscopy attempt. Use both structured scoring systems and clinical gestalt to predict structural difficulty ("Can I get the tube in?") and physiologic difficulty ("Can they tolerate the attempt?").

| Component | What to Assess | Concerning Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Look Externally | Facial appearance, anatomy | Facial trauma, large tongue, beard, missing teeth, obesity, limited mouth opening, prominent incisors |

| Evaluate 3-3-2 | Anatomic measurements | < 3 fingerbreadths mouth opening < 3 FB mentum to hyoid < 2 FB hyoid to thyroid notch |

| Mallampati | Oropharyngeal view (when possible) | Class III-IV (only soft palate visible, or soft palate not visible) |

| Obstruction | Airway patency | Tumor, hematoma, abscess, foreign body, angioedema, epiglottitis |

| Neck Mobility | Cervical spine movement | C-collar, ankylosing spondylitis, spinal fusion, pain/guarding, rheumatoid arthritis |

HEAVEN complements LEMON by identifying factors that increase procedural risk:

Assess the patient's physiologic reserve and ability to tolerate apnea during intubation:

Recognize these patients as extremely high-risk for peri-intubation complications:

Consider awake intubation, delayed sequence intubation (DSI), or other modified approaches for these patients.

| Blade Type | Technique | Sizes | Best Used For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Macintosh (Curved) | Sits in vallecula, indirectly lifts epiglottis by lifting hyoepiglottic ligament | 3 (standard adult), 4 (large adult) | Most adult intubations; larger mouth opening |

| Miller (Straight) | Directly lifts the epiglottis by placing blade tip posterior to it | 2 (small adult), 3 (standard adult) | Anterior larynx, pediatrics, floppy epiglottis |

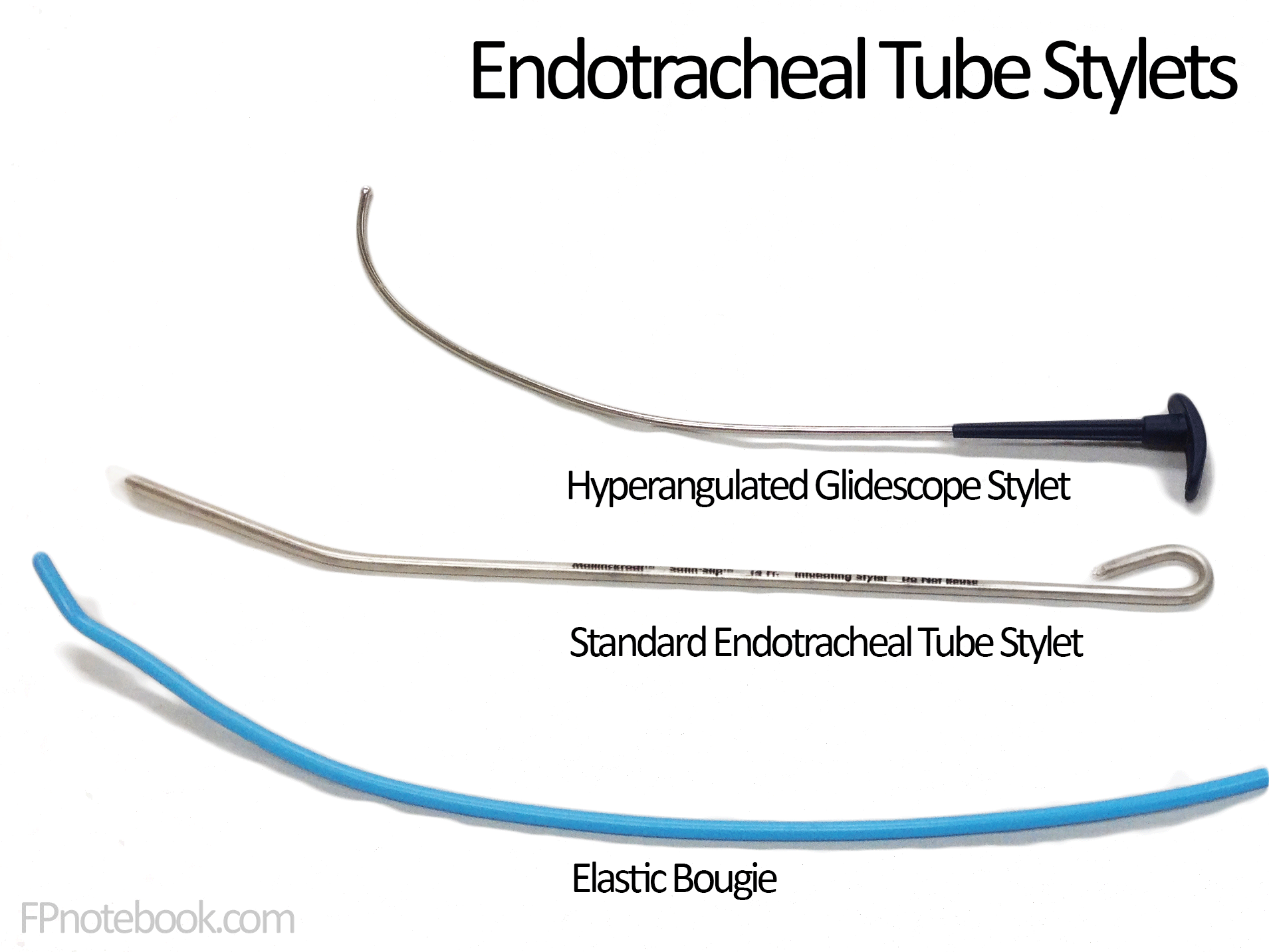

Stylet:

Bougie (Gum Elastic Bougie / Eschmann Introducer):

Suction:

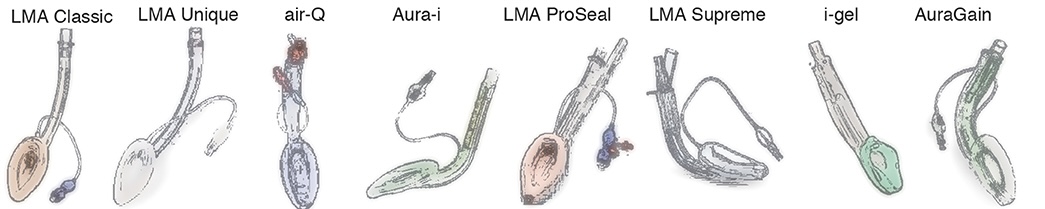

Supraglottic Airways (SGAs):

Before EVERY intubation, verify:

Before induction, conduct a brief team huddle:

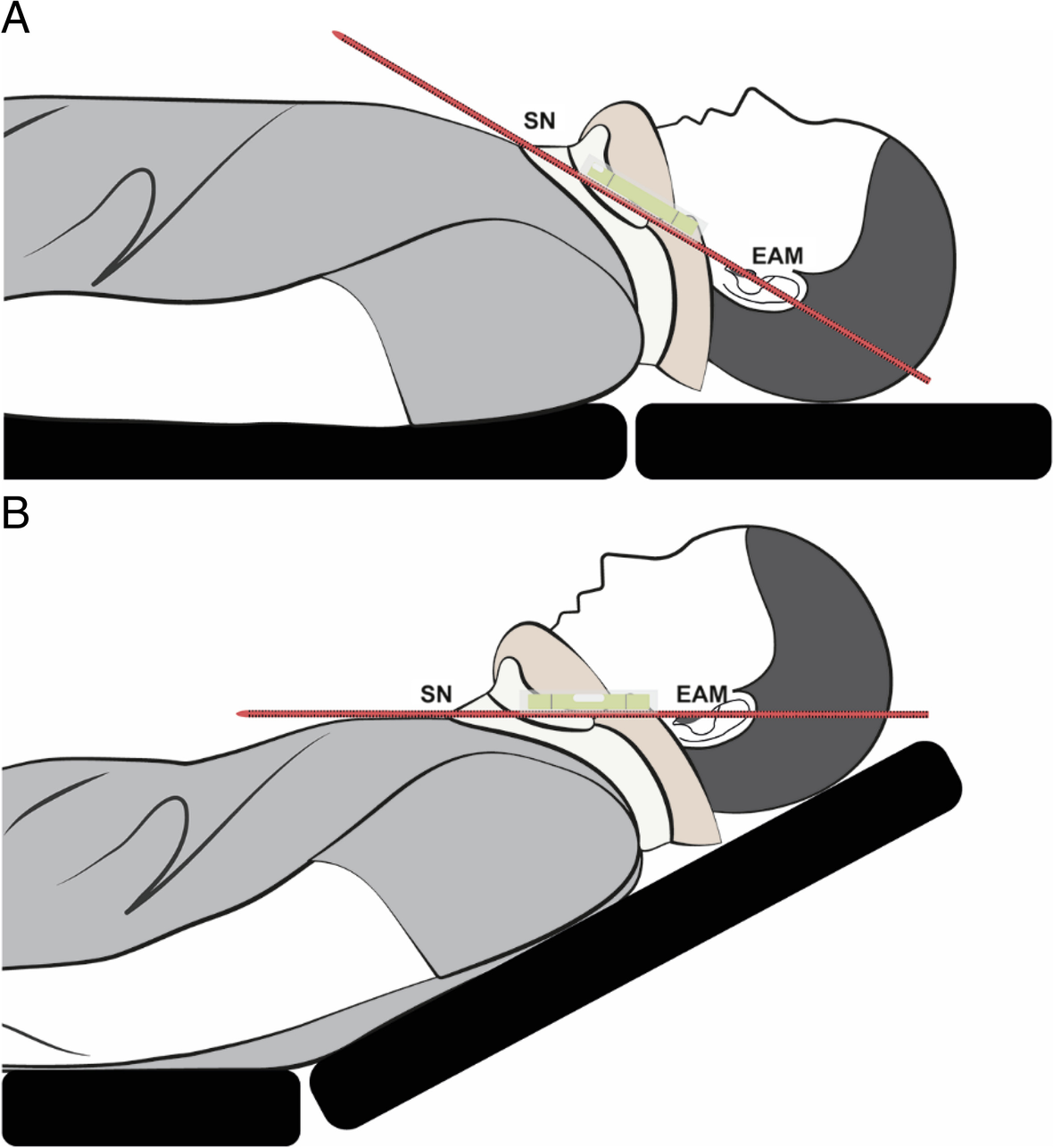

Ramped / Ear-to-Sternal-Notch Position:

Avoid flat supine positioning when possible:

Goal: Achieve SpO₂ ≥ 94% and maximize nitrogen washout to extend safe apnea time

The "sick, shocked, and pregnant" patient triad: These patients have dramatically reduced safe apnea times (often 1-2 minutes vs. 8+ minutes in healthy patients) due to:

Maximize preoxygenation time, consider delayed sequence intubation (DSI), and prepare for rapid desaturation.

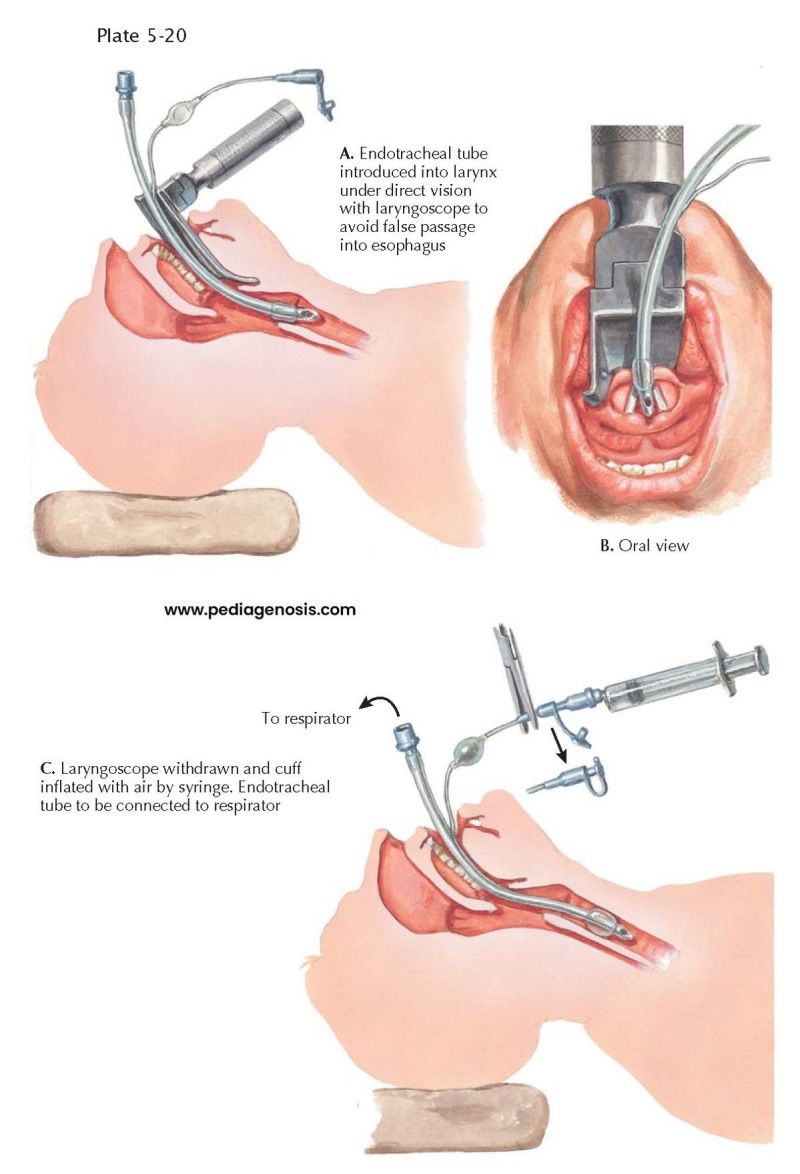

General Principles: Pre-brief that if SpO₂ drops below ~90% or attempt time approaches 20-30 seconds, the attempt will be aborted, BVM ventilation resumed, and the plan reassessed. RSI medications are chosen per your local protocol; this section focuses on the mechanical aspects of intubation.

Macintosh (Curved) Blade Technique:

Miller (Straight) Blade Technique:

Optimize the View:

If you have a good view (Cormack-Lehane Grade 1-2a):

If only partial view (Grade 2b-3: see arytenoids or epiglottis tip):

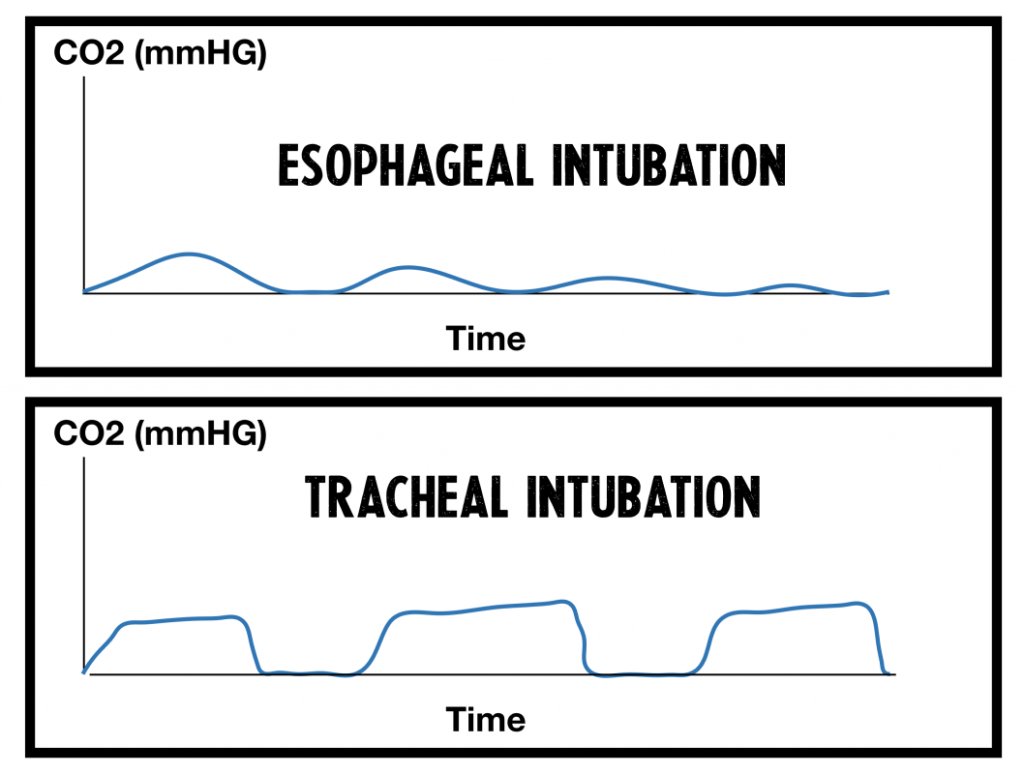

Primary confirmation - MUST HAVE:

Secondary confirmation:

Document:

The right mainstem bronchus is more vertical than the left, making it easy to advance the tube too far. Signs of right mainstem intubation:

Fix: Deflate cuff, withdraw tube 1-2 cm while auscultating, reinflate cuff, reassess. Typical adult depth is 21-23 cm at teeth (3x ETT internal diameter is a useful rule).

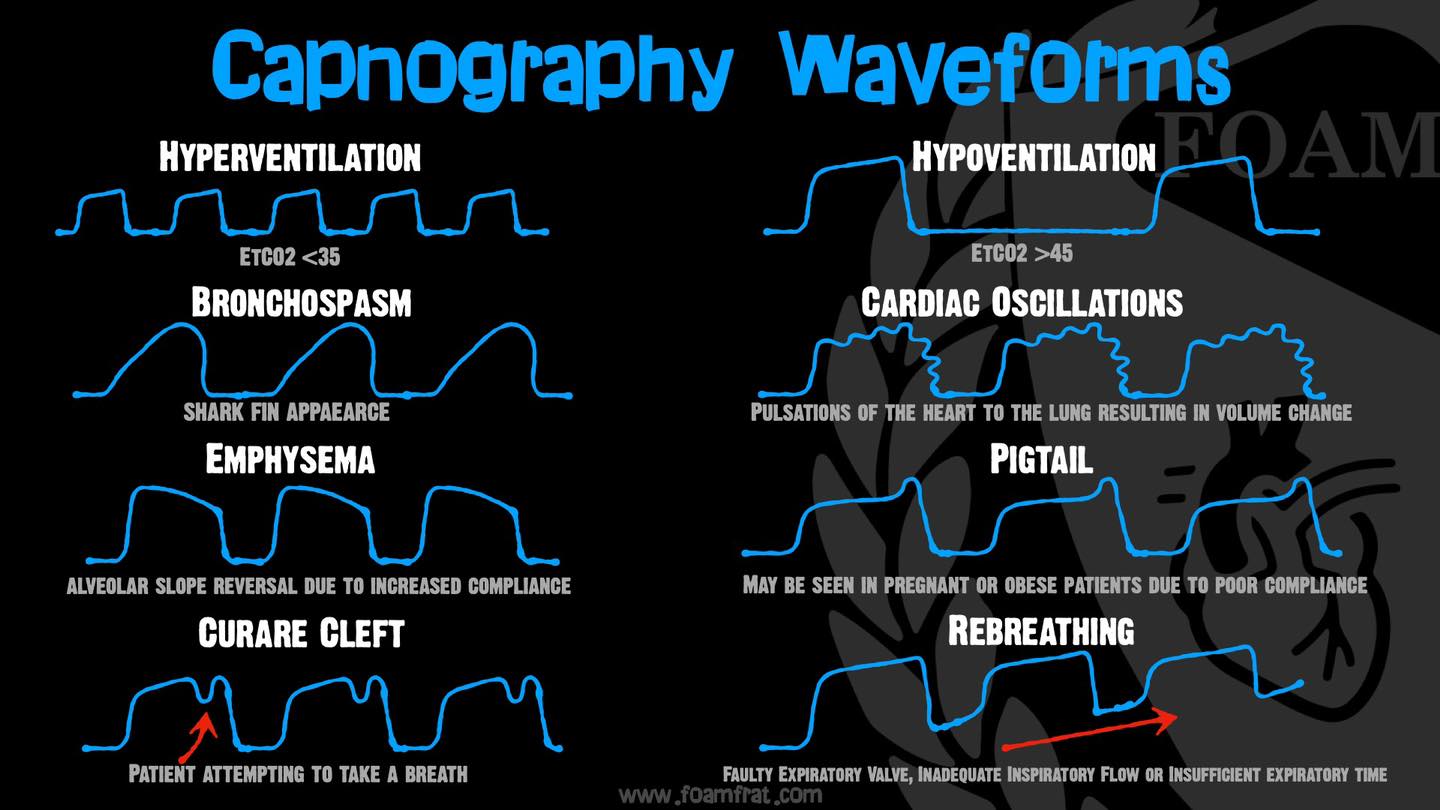

Capnography is the primary tool for confirming endotracheal tube placement and monitoring ongoing ventilation status. Waveform analysis provides real-time feedback on tube position, ventilation adequacy, circuit problems, and patient physiology.

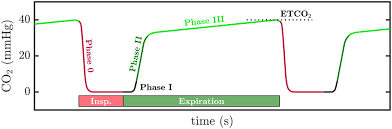

Four phases of normal waveform:

Normal EtCO₂ values: 35-45 mmHg in a perfusing patient (slightly lower than arterial PaCO₂ due to alveolar dead space)

Think DOPE/DOPES:

| Problem | Signs | Action |

|---|---|---|

| Dislodged tube | Sudden loss of waveform, absent breath sounds, gurgling over stomach | Remove tube, reoxygenate with BVM, re-intubate |

| Obstruction | High peak pressures, no chest rise, kinked tube, biting, mucus plug | Suction, pass catheter through tube, adjust bite block, bronchodilators if bronchospasm |

| Pneumothorax | Unilateral absent breath sounds, hypotension, high pressures, neck vein distension | Needle decompression or chest tube, reassess ventilation |

| Equipment failure | Check capnograph, circuit disconnection, ventilator malfunction | Switch to BVM, replace circuit, check all connections |

| Stacked breaths / hypoventilation | Auto-PEEP, inadequate expiratory time | Decrease respiratory rate, increase expiratory time, check for air trapping |

EtCO₂ during CPR provides real-time feedback on resuscitation quality:

For average adult (ARDS or general critical care patient):

Continuous monitoring:

Periodic assessments:

Common and dangerous complication occurring in up to 25% of emergency intubations. Causes include:

Prevention/Management: Optimize volume status before intubation, use push-dose pressors, minimize PEEP/respiratory rate if hemodynamic instability develops.

Re-optimize positioning:

Change equipment:

Improve the field:

Use a bougie early:

Adjust the tube/stylet:

Optimize visualization:

Consider bougie-assisted:

Prioritize oxygenation over intubation:

Place supraglottic airway early (Plan B):

Alternative intubation strategies:

Declare CICO emergency out loud:

Criteria for declaring CICO:

Proceed immediately to surgical airway (Plan C):

Multiple failed attempts with worsening hypoxemia, hypotension, and acidosis create a vicious cycle. Each attempt becomes more difficult as the patient deteriorates. Prevent this by:

"Failing to plan is planning to fail" is never more true than in emergency airway management.