Cardiopulmonary Support & Monitoring

Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO)

VV & VA Extracorporeal Life Support | ICU Reference for Critical Care Paramedics & Nurses

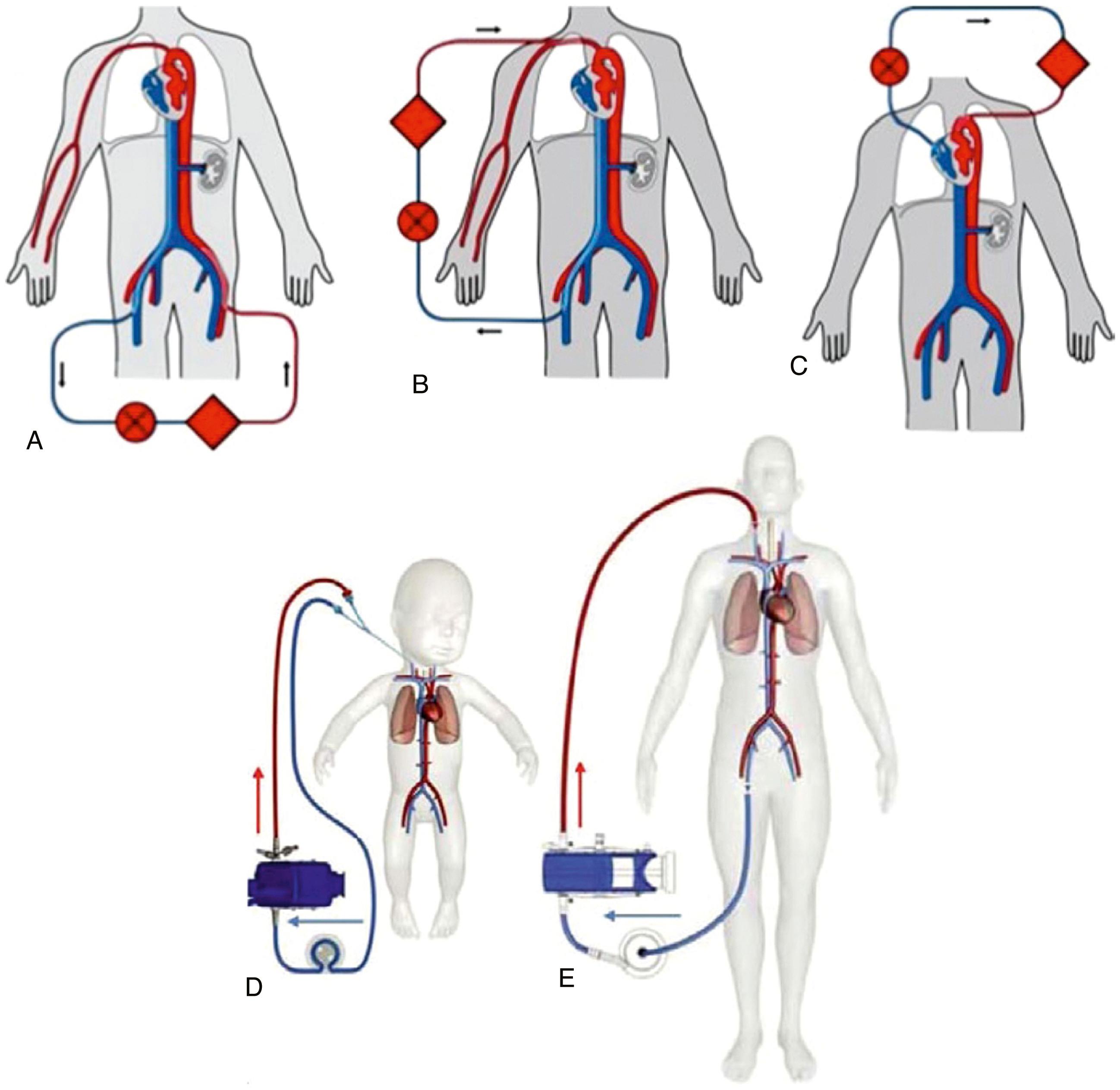

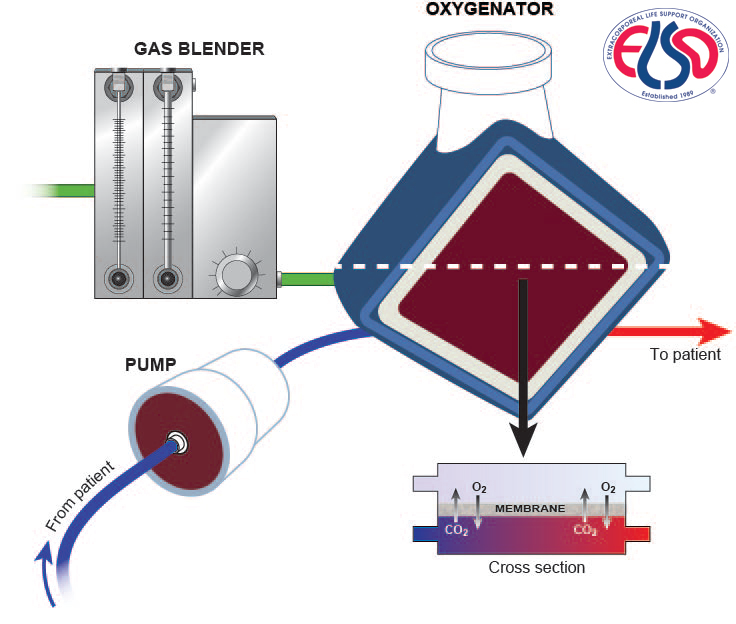

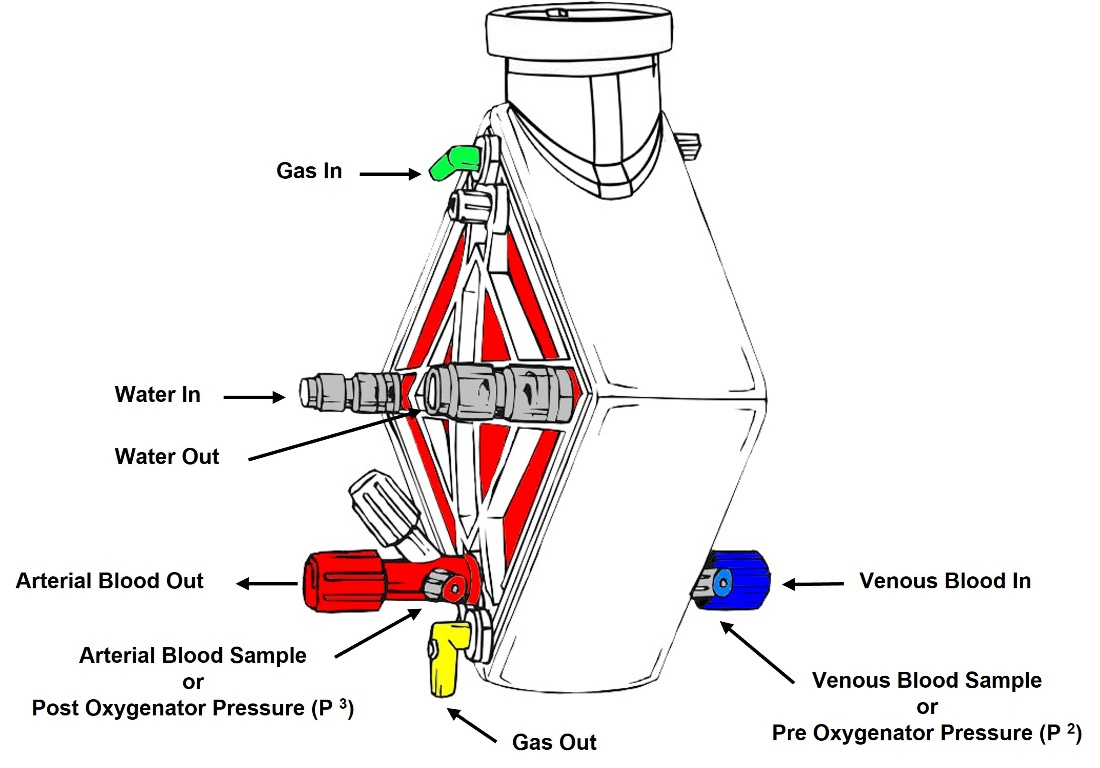

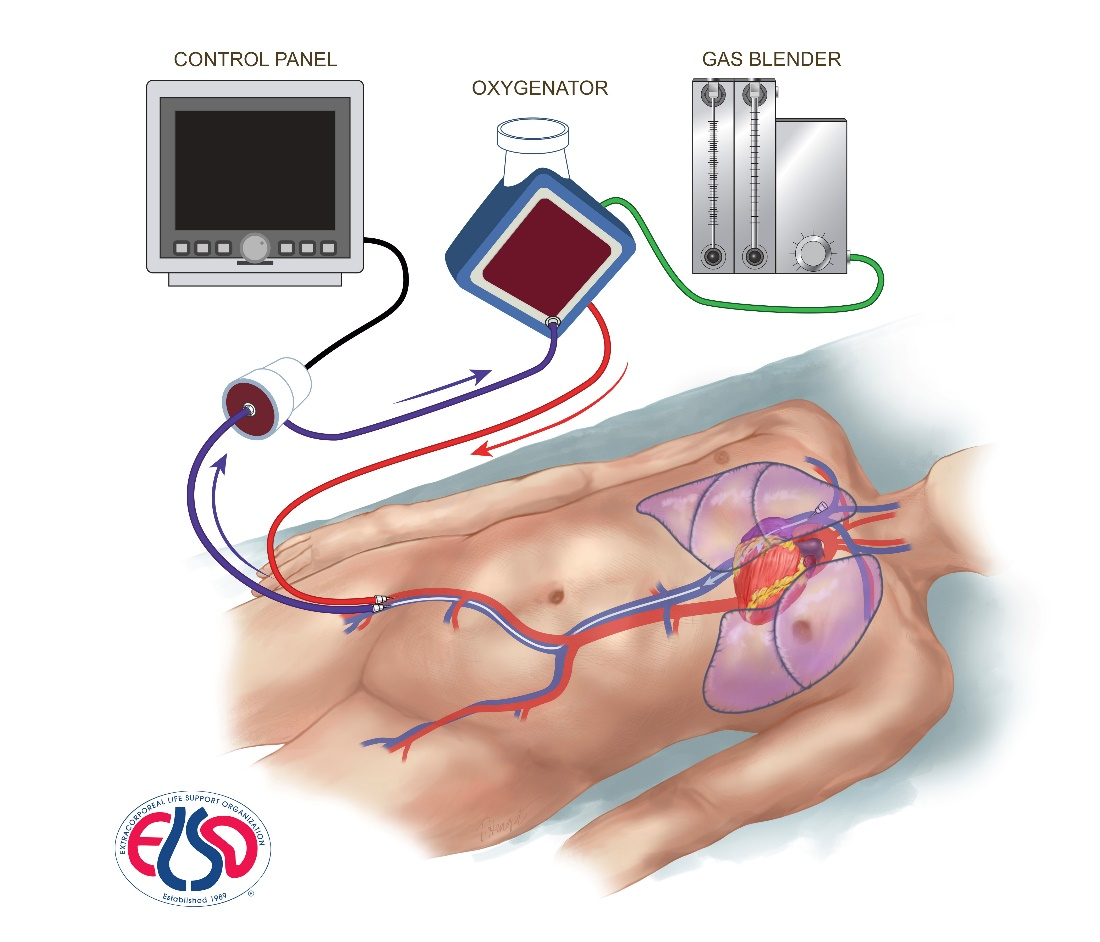

VV

Respiratory Support

VA

Cardiopulmonary Support

3-5 L/min

Typical Flow