Mechanical Circulatory Support

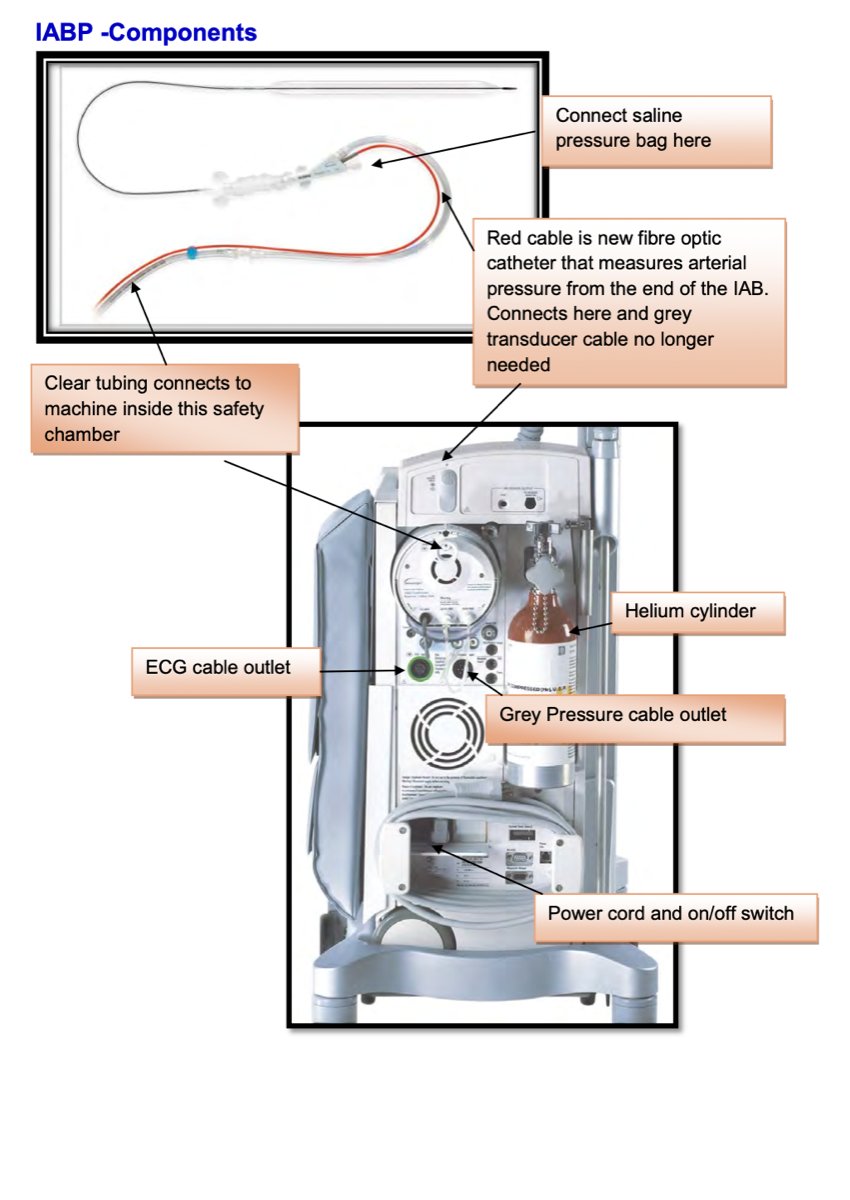

Intra-Aortic Balloon Pump

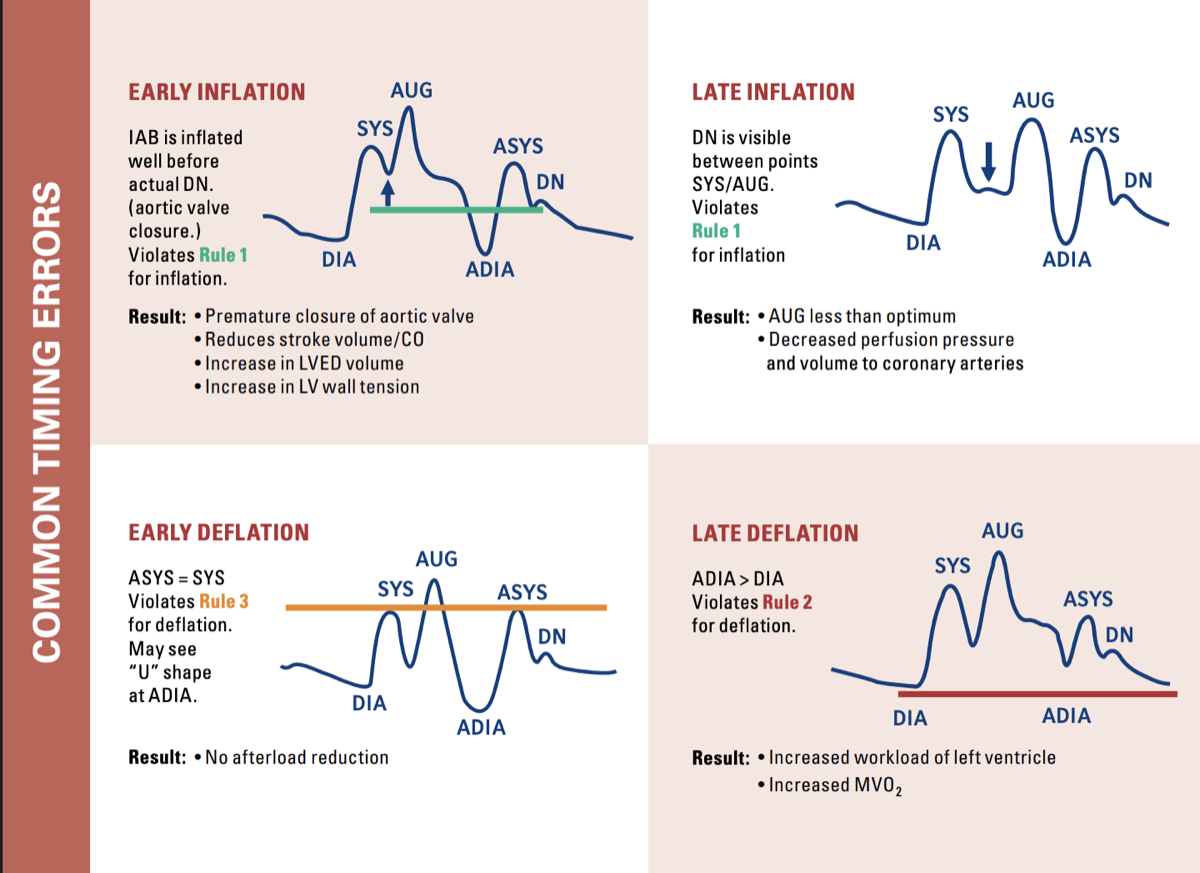

Counterpulsation device for LV support. Diastolic augmentation increases coronary perfusion while systolic deflation reduces afterload.

25-50mL

Balloon Volume

Helium

Inflation Gas

0.5-1.0

L/min CO Gain